If there’s one thing the Vuelta a España is known for, it’s climbing. The organisers of the Spanish Grand Tour can never be accused of going easy on the riders and not presenting enough opportunities for the mountain goats, and this year is no different, with no fewer than nine summit finishes included. Any rider hoping to win the red jersey will have good climbing legs from start to finish, and have many mountains to conquer before they can lay claim to victory.

But though the climbs of the Vuelta rival those found at the Tour de France and Giro d’Italia in terms of difficulty, few have attained the same mythical status as the most famous from those Grand Tours. This year in particular, in the absence of notorious names like the Alto de l’Angliru and Lagos de Covadonga, the assortment of climbs features many little-known or unknown quantities, while the parcours as a whole is defined more by the sheer quantity of hard climbs, rather than a select few highlights.

That said, there are still a few that stand out, and are likely to be the toughest and most decisive of the race.

STAGE EIGHT - COLLAU FANCUAYA

As home of the Alto de l’Angliru, the north-western region of Asturias often hosts the most thrilling battles of the Vuelta, and though its most famous mountain is bypassed this year, back-to-back stages here at the end of the first week are set to see the first major tussles in the GC race.

Of the two stages, the former on Saturday looks the toughest. Both are similar in terms of the quantity and difficulty of climbs that precede their summit finishes, with stage eight featuring five as opposed to stage nine’s four. But though the Colláu Fancuaya can’t quite match stage nine’s 13%-averaging Les Praeres in terms of steepness, the sustained effort required to keep going for a climb that is over twice the length means the time gaps are likely to be bigger by the top.

Colláu Fancuaya profile (Unipublic)

About 4km into Colláu Fancuaya is where the legs will really start to burn, as the gradient ramps up into double digits, at one point reaching a truly agonising 19%. The worse news is that upon completing this stretch, they’ve still half the mountain to climb, and therefore can’t afford to go into the red just yet. The final half continues at inclines mostly over 9%, bringing the overall average of the climb up to 8.5%, making this the first serious test for the GC hopefuls.

STAGE 14 - SIERRA DE LA PANDERA

Located in the Sierra Sur de Jaén mountain range, in the heat of Spain’s southernmost region of Andalusia, the Sierra de la Pandera is a real brute, and the first of the most important double-header of stages in the Vuelta. It’s the kind of climb that’s impossible to get into a rhythm during, with rough roads and double-digit gradients at the bottom preceding a slight easing off, which is followed by yet more extreme ramps.

In total, it averages 7.8% for 8.4km, but these stats only tell half the story. Before reaching the foot of the climb, the riders first have to climb the category two Puerto de los Villares, which is itself a serious mountain in its own right, lasting 10.4km at 5.5%. With barely 3km of valley roads between the end of the first and start of the latter, it’d be more accurate to see these climbs as one big mountain, and therefore one of the longest sustained efforts of the Vuelta.

Sierra de la Pandera profile (Unipublic)

Having featured five times since its debut in 2002, La Pandera will be familiar to some of the riders — none more so than Alejandro Valverde, who has featured in all but one of those occasions. The veteran Spaniard has been one of the definitive riders of the past two decades of the Vuelta, and inevitably has usually been centre stage on the climb, winning the stage here in 2003, losing crucial time to his GC rival and eventual victor Alexander Vinokourov in 2006, and defending his GC lead in 2009 en route to overall victory. How will he fare this time, in what will be his last ever Vuelta?

STAGE 15 - SIERRA NEVADA

By just about every metric, the Sierra Nevada is the hardest mountain of the Vuelta. At 2,521 metres above sea level, it’s the highest point of the race (even if the organisers haven’t been permitted to send the riders even higher up); at 19.3km it’s also the longest summit finish, and its average of 7.9% is among the highest; and it’s the only climb to have been assigned the ‘especial’ category.

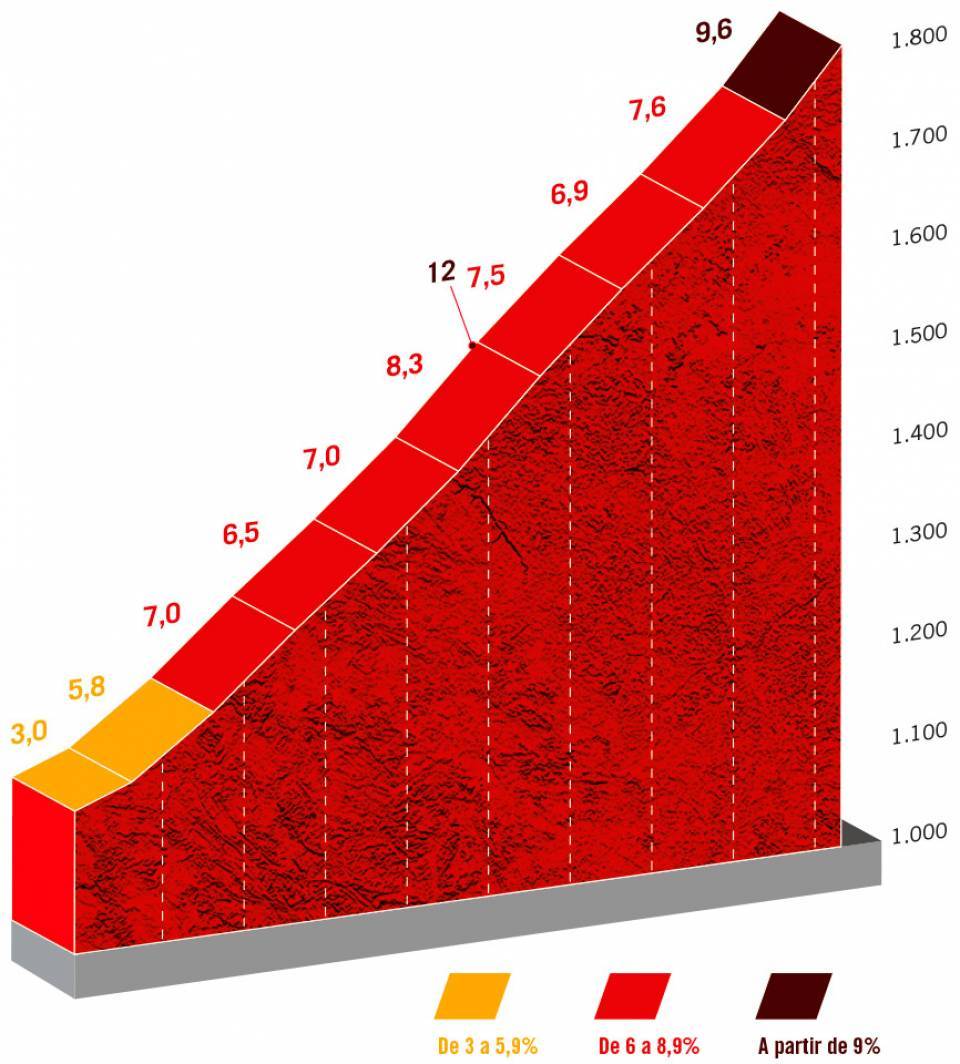

Sierra Nevada profile (Unipublic)

The mountains last featured at the Vuelta in 2017, when Miguel Ángel López dropped Alberto Contador to win the stage, while Chris Froome successfully defended the red jersey following an attack from Vincenzo Nibali. The damage was limited that day, with the first ten riders separated by little more than a minute, but this time the climb will be tackled via the far tougher route of the Alto de Hazallanas. At 7.5km long and averaging a horrible 9.6%, the Hazallanas is a brutally difficult climb in its own right, and was in 2013 enough for surprise overall winner Chris Horner to put over a minute into all of his GC rivals and gain the red jersey. When you consider that the riders will still have over 12km left to climb upon reaching the top of the Hazallanas, up what are relentless roads that still hover around 6 or 7%, the damage caused here could be irreparable.

STAGE 20 - PUERTO DE LA MORCUERA AND PUERTO DE CORTOS

From the start of the final week to now, the penultimate stage of the Vuelta, there aren’t any huge mountainous stages, with the Alto de Piornal on Thursday’s stage 18 being the only category one climb tackled in that time. But although the GC might therefore seem fairly set following the Sierra Nevada challenge, there’s enough in store on this excursion through the Sierras surrounding Madrid to cause a late twist before the race reaches its climax in the capital.

Puerto de la Morcuera profile (Unipublic)

There are five climbs in total, the most difficult being the final two: the Puerto de la Morcuera, and the Puerto de Cortos. On one hand, they don’t compare with the mountains discussed above in terms of gradients — the Morcuera only features a few stretches that exceed 8% and averages 6.9% across its total length of 9.4km, while the 10.3km Cortos doesn’t really get going until halfway up, at which point the slopes still rarely rise above 8%. Neither do they contain any nasty surprises, with each climbing at a steady rate devoid of the kind of sudden ramps upwards that characterise many of the Vuelta’s other marquee climbs, and the roads mostly being wide and well-paved.

Puerto de Cotos profiles (Unipublic)

But in the context of a stage that features such a relentless amount of climbing beforehand, they are still long and hard enough to cause carnage. Just look at the penultimate stage of the 2015 Vuelta, which also featured the same two climbs at the end, and where race leader Tom Dumoulin was dropped on the former, and cracked completely on the latter to fall out of the top five altogether.